“Death is Not the End” Bob Dylan posited in 1988, and in music the Great Beyond remains a lustrous realm. In tackling the cutting short of life, love, hope or a hundred other brands of demise, songcraft has so often found its most anguished, impassioned and heartfelt voice. Death’s songbook, indeed, is a rich maelstrom of emotion, life at its most vivid.

“So much of the greatest art, certainly from my point of view, is intrinsically melancholic,” says Charles Hazlewood, founder and Artistic Director of the pioneering Paraorchestra, an award-winning conductor who has led some of the world’s most celebrated orchestras, and Sky Arts Ambassador for Music. “Music which is about death, or the death of love, about loss, about anxiety, there’s a transcendence in that music. My go to, whether I’m feeling happy or sad or somewhere in between, will be melancholy music because that’s where the catharsis is, that’s where art is most resonant.”

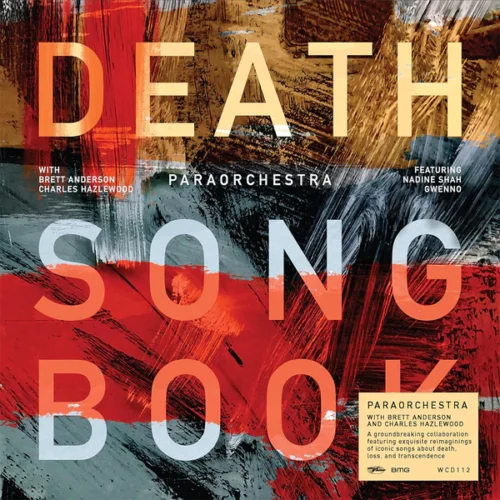

During the pandemic, when death was an enveloping presence reduced to unimaginable numbers daily, Charles was struck by the idea of an album of “very delicate re-clothings” of the most morbidly beautiful and poignantly sombre songs from his youth, entitled Death Songbook. “The only rule,” he says, “is that all the songs have to have a relationship to death or the death of love.”

Further inspiration came as a result of 2019’s Festival of Death and Dying – a weekend of music, poetry, performance art and discussion held in Somerset, intended to encourage a society which accepts the inevitable and celebrates the life left behind – Charles began mulling over one of society’s last great taboos. “We are horrified by death for good reasons,” he says, “but we don’t like talking about it, we don’t like thinking about it, we don’t like staring it in the face. And yet it’s the one thing that all of us will have to go through.”

He envisioned Death Songbook as a collaboration with Paraorchestra, of which he is Artistic Director: an ensemble consisting of professional disabled and non-disabled musicians playing an unconventional mix of traditional orchestral, acoustic, and electronic instruments and using assistive technology. The intention of this radical group is to reimagine what an orchestra – and “classical music” itself – can be in 2024. “It always seemed strange to me that the orchestra got a bit stuck in terms of its makeup in the late 19th century and it didn’t continue to evolve,” Charles argues. “It didn’t continue to embrace new musical instruments and new sonic spectrums that have emerged since. Why wouldn’t you want ranks of analogue synthesisers, digital equipment or assistive technology? These are all absolutely vivid parts of our current sonic constellation so they form part of our orchestra.”

Charles discussed his thoughts with nearby neighbour and friend Brett Anderson of Suede, who found it a concept close to the more shadowy corners of his heart. “I thought it was a lovely idea,” says Brett. “I’ve always found dark material more inspiring than upbeat songs. Upbeat songs always make me depressed somehow. I’ve always liked those songs that deal with the murkier sides of life.”

Together they scoured the catalogues of Depeche Mode, Echo & The Bunnymen, Black and Japan. “It was about the music that was really important to us when we were growing up,” says Charles. “Music with this theme in common of loss, anxiety, and desolation. The Eighties seemed to be all about desolation in many ways…there were so many reasons to feel despondent. During the Thatcher years, there was some phenomenal music coming out of our little island and with good reason – we had a lot to kick against.” “When you’re young, you’re probably at your most romantically tragic,” Brett adds.

Other eras bled in too. They reworked classic Sixties paeans such as Jacques Brel’s “My Death” and Skeeter Davis’s forlorn “The End of the World”, and Brett realised that he too had written several songs perfect for reinterpretation for the project. “There are so many songs that I’ve written where the initial thing was kind of about death and sadness and there’s so many songs that I wanted to re-interpret,” he says. “Things like ‘The Next Life’ which I wrote about the death of my mum, and there’s a solo song called ‘Unsung’, one of my favourite songs I’ve ever written, which I wrote about my friend who killed himself. Something like ‘He’s Dead’, it’s an interesting song to reinterpret using an orchestra. The original sounds like a little band in a rehearsal room, recorded pretty cheaply, but when you’ve suddenly got marimbas and strings and oboes on it, it takes on a completely different quality, which I quite liked.”

Paraorchestra recorded the majority of Death Songbook in an afternoon at the peak of lockdown in January 2021, socially distanced across Europe’s largest opera stage – the Donald Gordon Theatre at the Wales Millennium Centre in Cardiff. “There’s this lonely little group of 13 musicians in a huge wide circle on this vast empty stage in this vast, empty auditorium,” Charles recalls. “There’s something quite bleak and poetic about that in itself.”

Brett’s vocals dripped poetry too, by turns haunted, chilling, passionate and wracked with desolation, and several special guests added their own dark magic. Seb Rochford, known for his work with Polar Bear, Pulled by Magnets and Sons of Kemet, and Portishead guitarist Adrian Utley joined the ensemble for the project while regular Paraorchestra collaborator Nadine Shah added sumptuous additional voice to several songs. “Their talent is insurmountable and I love to sing with them,” Shah says, describing the Death Songbook session as “a moment of melancholic magic with a bunch of fellow goths”. “We benefited immeasurably from their generosity of spirit, and their sonic imagination,” Charles says of his venerable guests.

Charles’s reclothings – articulated by composer/orchestrator Charlotte Harding – meanwhile, are things of maudlin and menacing wonder. Unafraid of avant-garde or experimental rock methods, Paraorchestra offer little in the way of over-reverent adornment, instead masterfully twisting, contorting and reconstructing the songs to bring out the blackness within. The Bunnymen’s “The Killing Moon” becomes an unsettling concoction of shivering strings and stalking electric guitar, rising to a climactic tempest of drums. Skeeter Davis’ heart-shattered “The End of the World” is lifted into the sublime by Shah, as enveloping as death’s warmest embrace.

Songs from Brett’s catalogue are also stunningly reimagined; “The Next Life” is sensitively orchestrated, “Unsung” blossoms into an austere showstopper and Suede B-side “He’s Dead” builds from Arabian textures into an avant rock freak-out worthy of The Velvet Underground or Goat. And Japan’s “Nightporter”, all breathy Wurlitzer piano, creeping woodwind and haunted forest atmospherics, is a particular labour of love.

“It’s a strange mini-symphony or a mini-ballet all of itself,” says Charles, once an eyelinered teenager in the David Sylvian vein. “I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of what would happen if you reclothed that song, but at the same time inordinately nervous because you mess with your icons at your peril.”

Charles and Brett became so embroiled in the project that they decided to work up an original song of their own, sketched out in Charles’s studio. “Brutal Lover” is a plangent piano piece with dark classical overtones, performed on a “fucked-up old bar-room piano” with the hammers hitting tissue paper with a sour resonance. Bruised and broken, Brett’s portrait of domestic violence and its dehumanising aftermath could be read as an accusation from beyond the grave.

“It keeps ratcheting up a semitone at a time,” says Charles, “which gives a sense of heart-stopping panic that perhaps is part and parcel of impending loss or the moments before heartbreak. But it has moments of great stasis and grace.”

These initial recordings for Death Songbook were broadcast as part of the 2021 Llais festival, held online due to the pandemic, and were so well received that the project returned to the Wales Millennium Centre for a live performance in October 2022. Here they recorded three additional live songs to round out the final Death Songbook album. Excited to be working with Charles and Brett on “gorgeous arrangements of songs that embrace death in all its facets”, Gwenno provided guest vocals on a skittering, jazzy remake of Depeche Mode’s “Enjoy the Silence”. Brett delivered a devastating solo rendition of Jacques Brel’s “My Death” to Adrian Utley’s electric guitar. And Paraorchestra rocked out on a grungy, garage punk take on the lead single from Suede’s recent Autofiction record “She Still Leads Me On” – another tribute to Brett’s late mother.

What has emerged is a record of great emotional charge, deep fragility, elegant invention and broad thematic sweep. While some songs directly confront the Big Sleep, a surrealist beauty such as Mercury Rev’s “Holes” is included for its swells of limitless sadness. “There’s this sense of regret about it that resonated with me,” Brett says. “That line about ‘holes, dug by little moles’, there’s something so sad and childlike about that.” And Black’s “Wonderful Life” is a welcome moment of uplift, whether you interpret it as an anthem of defiant positivity in the face of heartbreak or take your clues from the tremulous dulcimer that darker matters are afoot. “It’s so brilliantly, bleakly ironic,” says Brett, “that’s why I love it.”

Death Songbook, after all, is open to all shades of grey. “We want to celebrate heartbreak, misery, anxiety, loss, desperation,” says Charles, “because some of the very greatest music ever created from JS Bach to Mozart to Mahler to Shostakovich stems from the same theme.” Forget the devil, it’s the reaper who has all the best tunes.